ONLY THE WORDS CONTINUE / IN THIS WAITING /

CLOSE YOUR EYES AND YOU WILL SEE

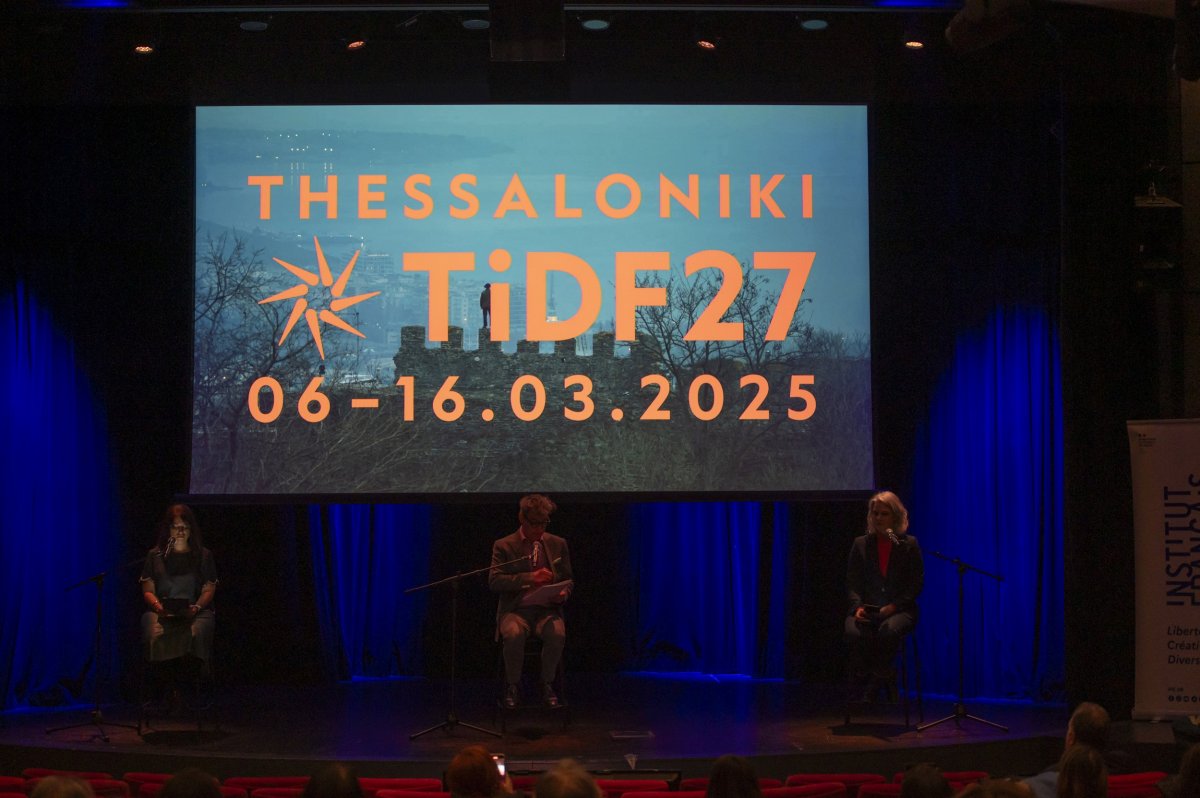

On Wednesday, March 16, as part of the 13th Thessaloniki Documentary Festival, a Press Conference was given by the directors Kalliopi Legaki (Only The Words Continue), Anna Tsiarta (In This Waiting) and Stavros Stratigakos (Close Your Eyes and you Will See), whose films are participating in the international program of the Festival.

Kalliopi Legaki’s film, Only the Words Continue – a mosaic of people’s confessions – was inspired by her collaborator Alkis Gounaris, who began his project “The Confession Session” in the winter of 2010, recording the confessions of patrons of the bar Dassein, in Exarheia. “Alkis’ idea made me think about the meaning of confession. It’s amazing to observe human speech. Each person’s attitude shows his character, his way of thinking, his feelings”, the director said, and explained that the film’s title was inspired by a verse from poet Matsuo Baso, “only my dreams continue”. “Seeking a way to connect these confessions, I thought of scenes from the city and the daily life in the bar. By accident I found a book by Baso in my library, and thought that this completely different form of talking can be cathartic, because it comes from a completely different culture, elements of which I included in the film”, she said. About the immediacy that makes the viewers almost feel they are eavesdropping through a wall, she noted: “Sometimes I think that not only do people not eavesdrop, but they don’t hear at all, not even the person across from them. The people confessing speak to the camera spontaneously. And the good thing is that no one regretted anything they said, there was no guilt”. She continued: “Even if the feeling the viewer has about what he hears can be considered voyeuristic, why should we mind the word?” At the end of the film the director walks in front of the camera and makes her own confession. “Through the process of the other confessions, I felt the need to speak as well. It was a demonstration of honesty to the people who spoke in front of the camera”, Ms Legaki said.

Some two thousand Greek and Turkish Cypriots went missing during the bi-communal conflicts of the 1960s and the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974. Seven relatives of these missing recall their harrowing stories: from their last moments together until recent exhumations began to shed light on the possible fate of their loved ones. Director of In This Waiting, Anna Tsiarta, talked about her film: “I went to the funeral of a friend’s father, and it was a moving and strange experience. People were at a loss, didn’t know how to react, whether to cry or feel relief that there was closure after 33 years. Cypriot society was in shock for the whole summer of 2007, the government tried to keep things low-key; journalists didn’t pay much attention to the issue. I felt I had to do something”, she said. Asked about how she managed to keep her objectivity, since she is Greek-Cypriot herself, she noted: “It isn’t easy at all to be a neutral observer. Luckily, I collaborated with an American woman who reminded me how important it was to stay objective. But I received many comments from Turkish-Cypriots that my film is Greek-Cypriot propaganda. While on the other hand, Greek-Cypriots told me that my film devotes too much time to the Turks, while their side suffered the most”. She researched material from foreign television channels such as the BBC, wanting to see how the events were covered by foreign observers. “I was outraged by many elements of the story, sometimes I thought I was making the wrong documentary and that I should be making a political film about all that happened. But I believe it is more important to make a film that records what these people went through, spending their lives with the hope and the uncertainty as to whether their loved ones were still alive”.

Director Stavros Stratigakos, in his film Close Your Eyes and you Will See brings to light rare archival footage on the history of radio in Greece. His research in the archives of ERT (Greek State TV) began as a result of a book published by the Greek Radio Institute in 1961. As he said, even though radio existed in Greece since 1930, it was only in 1952 that broadcasts began to be recorded. “Whatever was made before then was lost”, he mentioned. Mr. Stratigakos’ film covers the period from 1952 to 1965, when television appeared. Even after 1952 “there are black holes in ERT’s archives, and many times my research stumbled there. Now there is an effort being made to digitize the material. This treasure belongs to the people” he said. Though he is a film director that works for ERT, Mr. Stratigakos believes that radio has a magic that television doesn’t have. “Television has an ego, it sets limits on imagination. As Empirikos said, it shows human beings as small, but with a big voice. Also, television downplays and abuses sound, makes it secondary to the image. In television you can’t escape from the realistic vestiges of the image”.

The documentary speaks about radio and its connection to popular songs, lyrical songs and theater. Asked whether such an immediate relationship between a communication medium and the arts has eclipsed, Mr. Stratigakos said: “Of course it has eclipsed. Many things have. You know, radio people of that era had morals. What Antonis Lavdas said is very true, that “we referred to Gounaris as the popular singer, we didn’t say the great, because what would we then say about Beethoven? Today, superlatives are used with unbelievable ease”.