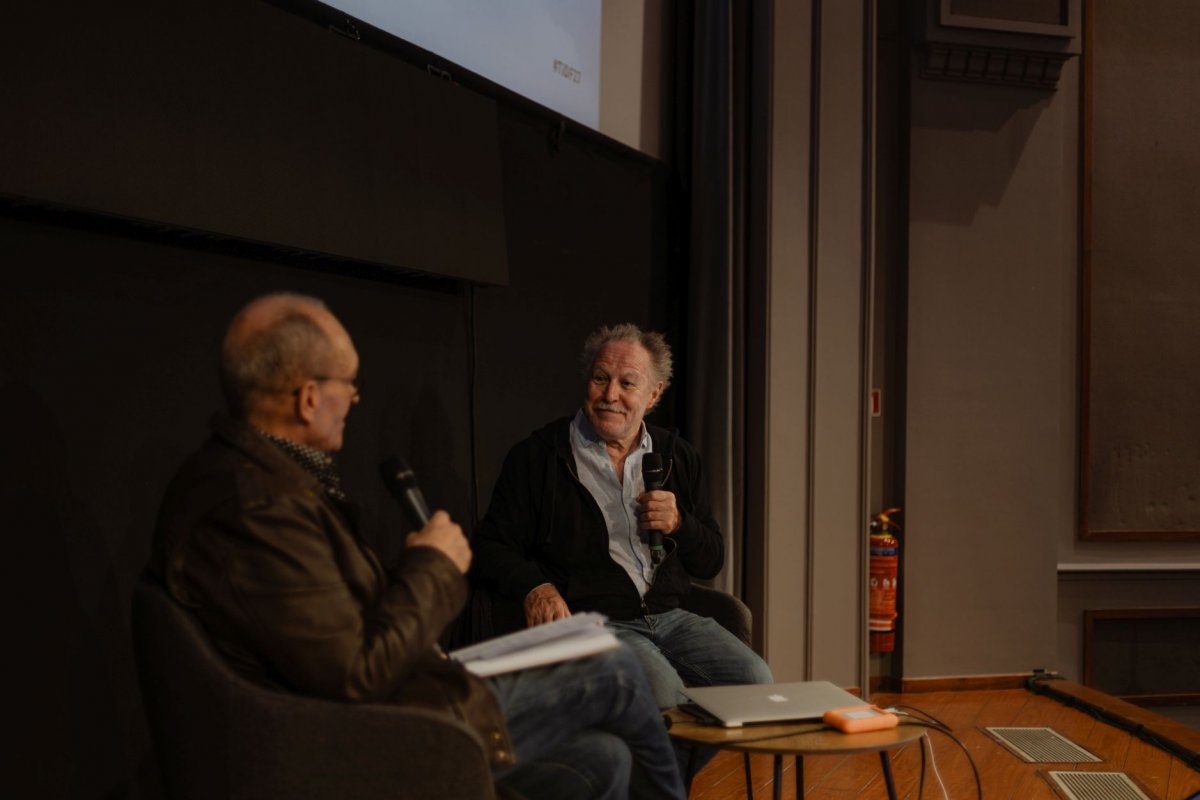

On Saturday March 8th, at Pavlos Zannas theater, the audience of the 27th Thessaloniki International Documentary Festival was given the chance to attend a captivating masterclass by renowned filmmaker Nicolas Philibert, this year’s distinguished guest. Widely celebrated as one of the most iconic documentarians of our time, recipient of the Golden Bear, a César Award, and a European Film Academy Award, Philibert has consistently delved into the enigmatic depths of human reality. In his masterclass titled “Improvise, an Ethical Necessity,” Philibert offered invaluable insights into his creative approach, highlighting the essential role of authenticity and the human gaze in observational cinema.

Opening the masterclass, filmmaker and moderator Marco Gastine welcomed the audience and Nicolas Philibert, briefly outlining the acclaimed French creator’s work and career, spanning from the late 1970s to the present day. Introducing the discussion, Marco Gastine pointed out that the conversation would be spontaneous and improvisational, fully aligned with both the title of the masterclass and Philibert’s overall directorial approach. “Philibert’s method is defined by his willingness to observe and share the emotions and words of people who differ from the norm, as well as his endeavor to understand them. One of the strongest characteristics of his films is that, by observing others, he simultaneously observes himself, turning the filmmaking process into an act of sharing,” he remarked.

Immediately afterward, Nicolas Philibert took the floor, warmly greeting and thanking the attendees. He began by emphasizing that the word "festival" ought to express and include everyone standing on the unseen side of art. Commenting on the widespread perception that fiction films and documentaries are entirely distinct fields, Nicolas Philibert responded: “People often ask me, ‘Documentaries are fine, but when will you finally make a real film?’ I turned to documentary filmmaking after I had already entered the world of cinema, a world I had always deeply loved. At that time, documentaries were scarce, and I had seen very few. When I made my first documentary, I started discovering and deeply enjoying the genre. Documentary filmmaking offers a vast creative space with thousands of ways to speak about the world. Although I’m not particularly enthusiastic about the label ‘documentarist,’ it is the one that has accompanied me throughout my career,” he noted.

In response to Marco Gastine’s question about the starting point of his creative approach to each new project, Nicolas Philibert emphasized that, for him, the most significant moment is always the very beginning. “To create a film, you need a solid starting point, a springboard. However, when I actually start filming, what I don’t know is where the film will eventually take me. I often tell my students: the film itself will guide you. It doesn't even primarily matter what the subject is; to me, there are no good or less good, major or minor topics. You can create compelling films about small, seemingly mundane subjects, just as you can make indifferent films about grand issues. The beauty of a film is not proportional to the magnitude of its subject. For instance, my film On the Adamant is not truly about mental health, but rather a documentary about the patients themselves. I want to feel confident that I have full access to the microcosm of each story and the freedom to observe what happens day by day. Also, I need to be sure — even though this can be challenging — that a strong relationship of communication exists with the people I'm observing. My goal is always to create aesthetic, political, and economic conditions that inspire the individuals in my films to genuinely offer something meaningful, both to me and to the audience. At the start of any project, it's impossible for me to know exactly what they will give; all I can do is listen carefully and try to understand. I begin with an initial idea and then gather whatever my protagonists choose to share, even if I have no idea beforehand what that might be,” he underlined.

Continuing the discussion, Marco Gastine highlighted the crucial role played by the carefully selected locations in Philibert’s work, as well as the challenges that might arise when approaching, for instance, psychiatric institutions. “Behind every location, there is a community of people. It’s extremely important for me to understand how they manage to coexist. This process unfolds differently with each film. Usually, it doesn’t take me long to pick up my camera. In the film To Be and to Have, the students were particularly spontaneous, so it took me very little time to start filming them. One day we gathered with the students, parents, and teachers, and the next day I arrived at the school with cameras. I let the students familiarize themselves with the equipment, and then we simply began working. In the case of On the Adamant, however, I didn't enter the floating structure directly with my camera, it would have been rude and intrusive. It took me some time to explain clearly what I was looking for, why I was there. I made an effort to convey to the people there that they had the absolute right to accept or decline participation. It also took me some time to explain what a film, screening, platform, or editing means, as I strongly believe anyone participating in a film should be fully informed. At times, people may require additional time to decide whether they wish to participate or not. Undoubtedly, it can be quite intimidating to suddenly find yourself with a large camera pointed directly at your face,” Philibert remarked.

When asked whether his improvisational approach has ever posed challenges in securing funding for his films, Philibert explained that he always remains honest with his funders about potential risks. “In my first film, I couldn't even say with certainty that I would manage to complete it. That’s why I openly describe my ideas, along with all the inherent risks and uncertainties involved, instead of merely presupposing future success. I prefer being honest to earn the trust of my funders, I never try to convince anyone that I have absolute control,” he stated. Responding to Marco Gastine’s question about how and when he decides to conclude filming and begin gathering material for the editing process, Nicolas Philibert replied: “Filming can go on endlessly. However, there comes a moment when editing emerges as an irresistible urge, a moment when I tell myself I now want to see clearly what I've gathered and how I can shape it”.

The conversation continued with the screening of a sequence from the film Trilogy for One Man (1987), which unfolds the story of a mountaineer who risks his life in front of the camera, attempting to conquer dangerous peaks. “I wanted to show you this particular sequence because nothing should ever be taken for granted. We had extensive discussions before we began filming. I wanted to understand how he felt about the camera, and to clearly explain that its presence should never push him to extremes, since even the slightest mistake could cost him his life. I didn’t want him to perform recklessly or attempt to surpass his limits merely because of the camera’s presence. Reality changes when it is captured. Filmmakers carry a responsibility towards the people who appear in their films,” Philibert concluded.

The masterclass proceeded with a dialogue between the filmmaker and the audience, during which Nicolas Philibert reflected on his studies in philosophy and the extent to which they influenced his work. “I studied philosophy for three years but never completed my degree. Certainly, this background expanded my way of thinking. However, my work isn’t rooted in any particular philosophical school of thought. I'm not trying to communicate a specific message through my films. When the intention to convey a precise message becomes too powerful, we tend to lose sight of the beauty inherent in making films. If everything is controlled and predictable, we set a trap for ourselves. Beauty emerges from the unforeseen, it’s the unexpected that illuminates a film, and that's exactly why improvisation becomes essential. My approach is rather simple: I attempt to understand and collect bits and pieces. There are moments when I try to understand my own motivation behind making a film. Sometimes, I even dare to admit that I ultimately did make a film just to comprehend my initial motivation. I might even complete it without ever fully grasping it,” Nicolas Philibert remarked.

Referring to a question posed to him yesterday during the ceremony in which he was awarded the honorary Golden Alexander, the French filmmaker responded: “Yesterday, someone asked me about the fog in the film On the Adamant. In my films, the ultimate conclusion always emerges through a sort of ‘fog.’ If I knew the final outcome from the very beginning, it would be terribly boring. That’s precisely why I avoid fiction. So, I wanted to conclude the film in fog and begin the next one in the same setting, although, due to climate change and urbanization, we hardly get any fog in Paris anymore,” Nicolas Philibert joked.

When asked how he connects with the individuals portrayed in his films, particularly patients in psychiatric clinics, Nicolas Philibert reflected: “I know nothing about their medical histories. I don't have the slightest clue about their daily routines or medication. After all, we aren’t specialists. Each of these films carries an inherently human dimension. They allow me to form genuine bonds, and often these relationships extend well beyond the completion of the film. Last year, for instance, a woman who appeared in my film In the Land of the Deaf (1992) came looking for me, thirty years after its initial screening. Particularly in psychiatric institutions, you encounter people who make it impossible to remain distant as they touch the very core of your existence. Documentary filmmaking itself is just like that: an open door leading directly to the unexpected”.